The developmental editor’s process

Every editor has their own way of working

Every editor has their own way of working

I’m sharing how I work, wearing my ‘developmental editor’s hat’, with authors who plan to self-publish, many of whom are new to the publishing process.

I use Scrivener for all my writing and, if that’s what the authors in my RedPen Mentoring group choose as their writing environment, I provide editing services for them in Scrivener.

I’m hoping some editors will consider providing the same service to this growing market. Then, maybe, I can retire!

How does a WIP land on my desk? What do I do first?

I ask authors to send their Scrivener project using WeTransfer. It’s a free online service.

I download the project and save it in a folder with the author’s name. Once I’ve done this, the author will receive a notification from WeTransfer that the file has been downloaded by me.

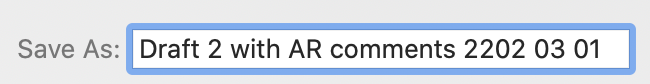

I then open the Scrivener project and make a copy of it, using File Save As, adding ‘with AR comments’ and today’s date in reverse format.

I work on this copy of the project and, eventually, send it back to the author using WeTransfer again.

Why do I create my own copy? If I don’t, and the author decides to continue working on the project (contrary to my suggestion that they take a break for a few days and wait for me to send it back), they will be warned by Scrivener that someone else is working on it and do they want to create a copy. This can unsettle the author …

As a developmental editor, what will I look at? What’s my process?

The first time I receive the project from a new author, I work on it for however long the author and I have agreed. This is usually at most two hours. That’s not a major investment for the author, but still enough time for me to identify what aspects of their WIP need most attention.

My process is then simple: take snapshots, stock check of content, read and provide feedback.

Taking a snapshot

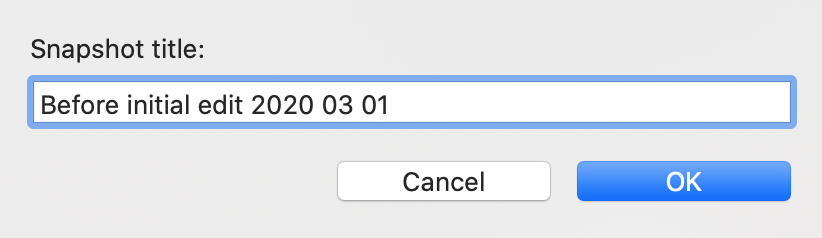

First, I take a snapshot of every document in the Binder and choose a meaningful title. (If you’re not sure how to take snapshots, check out this blog post.)

I’ll repeat this process just before I send the project back to the author. Then, the title will be ‘After initial edit’ and the date I finished.

Taking stock of what’s there

I’ll look at everything the author has provided: in the Binder, in the Editing Pane, and in the Inspector.

- In the Binder, I’ll see the manuscript, character sketches, setting sketches and whatever is in the Research folder.

- In the Editing pane, I’ll look at the Corkboard and the Outline view, as well as reading the text in Scrivenings.

- In the Inspector, I’m looking mostly for metadata, comments and notes.

I explained what I might expect to receive in a previous blog post. If anything is missing, my initial feedback to the author suggests they fill the gaps.

Reading and providing feedback

I read as far as I can, given the available time, editing as I read onscreen, using a range of Scrivener tools:

- Revision mode: This feature allows me to insert words (new or alternatives) and punctuation as necessary.

- Annotations are useful for highlighting material that I believe could/should be cut.

- Comments are highlighted in the text (in Scrivenings) and appear in the Inspector.

- Depending on what I find, I might create collections to help the author to find instances of material that warrant their attention.

My aim is to identify as many issues as possible – but not necessarily every instance of them. My feedback needs to be helpful – and not overwhelming – so I make also use of Scrivener’s colour coding options.

I’ll give examples, in a subsequent post, of how I use these tools – and how you can make best use of them too.

Setting tasks

As I say, it’s not my practice to overwhelm the author with feedback. New authors, in particular, react better to a small number of (achievable) tasks.

So, I identify three challenges/tasks for the author. This is in line with my RedPen Editing system – and I urge writers to purchase a copy of Editing the RedPen Way: 10 steps to successful self-editing. It’s only £2.99.

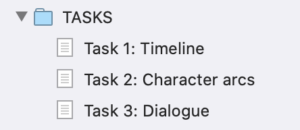

If the author hasn’t done so already, I’ll set up a folder for Editing Queries/Tasks within the Research Folder.

These tasks are numbered and labelled and, in addition to the three listed already, they often refer to standard topics:

- Big picture issues: Plot / Story structure / Chapter length

- Style issues: Pace / Point of view / Setting

- Devil in the Detail issues: Spelling, punctuation and grammar

I expect to see the project more than once, and can refer to this folder to see what advice I’ve given previously, and the response of the author, before I add my next three tasks.

The author can also use this folder to note tasks they have determined for themselves.

What happens next?

I send the project back to the author, completed with my suggested corrections, annotations and comments.

The author then works on the project some more, and I explain how they might process my feedback in a subsequent post.

I may not see the project again until the first draft of manuscript is complete. Between times, we have the option of online meetings. The author can ask questions, or for clarification, and we often brainstorm plot issues.

What’s my developmental editing style? Would it suit you? Would it suit your client?

The underlying concept of my editing work is to encourage my mentee to accept responsibility for every word on the page. I want them to produce the best book they can, and gain confidence in their writing/editing ability. Book 2 will be so much better than Book 1 …

I couch my advice as a question, rather than a directive. The writer then has to decide. It is their story after all. My aim is to steer them in the right direction, and – most important – for them to learn in the process.

So, if I think a character could be dropped, I don’t say:

Ditch Harry. He serves no purpose.

Instead, I’d say something along these lines.

It’s important for each character to serve a purpose.

It might help you to revisit your character sketches and consider which,

if any, might not be pulling their weight.

Harry, for instance. I’m not sure he really has a role.

Why do I adopt this approach? The first story I wrote and read aloud to a group of writers elicited a similar response: Ditch Sven; he serves no purpose. My reaction was to rethink the relationship between Sven and the main character. The net result was for Sven to be given a greater role. He was not dropped!

What’s in a writer’s head doesn’t always make it to the page. They ‘know’ things but the reader doesn’t find out because the writer omits to mention some salient point. So, if the text doesn’t make sense to me, rather than offer a solution (using incomplete information), I ask for clarification, and back it up with some relevant theory about writing.

How does Scrivener compare with Word for the editing process?

Editors using Word will use TrackChanges to record the editing they have done, and leave comments in the margin. This system ‘works’ and has been the industry standard for decades.

My experience, especially with a heavy edit, is that the margin cannot cope with the volume of comments, and the text looks such a mess, it scares an author. This level of overwhelm is avoidable if the edit is done in Scrivener, and in manageable stages.

Also, the author who writes in Scrivener and intends to self-publish from Scrivener, needs their project file to be the master version. It’s time consuming to export to Word and then process comments from Word, just because their editor prefers to use the ‘industry standard software’, and doesn’t (yet!) offer the same service in Scrivener.

Any questions? Need a helping hand?

I’m happy to explain more about my use of Scrivener for developmental editing and to answer your questions. Book a Simply Scrivener Special.

To help me to prepare for the webinar, please also complete this short questionnaire.

The ScrivenerVirgin blog is a journey of discovery:

a step-by-step exploration of how Scrivener can change how a writer writes.

To subscribe to this blog, click here.

You can also find links to blogs of specific topics in the Scrivener index.

Also … check out the Scrivener Tips.

No Comments